By Ambassador John Bolton

This article first appeared in the Washington Examiner on December 7th, 2022. Click Here to read the original version.

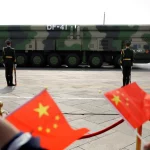

The “peaceful rise” of China as a “responsible stakeholder” in international affairs has long been Beijing’s mantra to conceal its extraordinary expansion of military capabilities. Its rapidly growing nuclear weapons arsenal, which makes it the third-largest nuclear power after Russia and America, urgently requires adapting U.S. nuclear and overall military strategy to respond to this increasing threat. This process has begun, but it remains dangerously inadequate and far too slow. The newly elected Congress provides a critical opportunity to raise the alarm about China, especially its nuclear capabilities.

Lulled for years by Deng Xiaoping’s stratagem “hide your strength, bide your time,” policymakers believed China sought only “minimal nuclear deterrence,” enough to deter nuclear attacks but not more. That is no longer true, if it ever was, as China replaces “hide and bide” with “wolf warrior” diplomacy. Testifying at his September confirmation hearing to lead the U.S. Strategic Command, Gen. Anthony Cotton said, “We have seen the incredible expansiveness of what they’re doing with their nuclear force, which does not, in my opinion, reflect minimal deterrence. They have a bona fide triad now.” By developing land, air, and sea delivery systems, China is acquiring a first-strike capability and the resilience to withstand a first strike and still respond with devastating nuclear force. This is not a “peaceful rise.”

The Biden administration’s nuclear posture review, in a declassified edition released later, agrees that America “will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries.” Incredibly, however, the review asserts this threat will arise “by the 2030s,” which is manifestly incorrect. We are there now.

Undoubtedly the hardest strategic problem is dealing simultaneously with two near-peer nuclear powers, both in terms of deterrence and, if need be, actually launching nuclear weapons on two fronts. Cold War deterrence theory essentially assumed a bipolar U.S.-USSR scenario. Incredible intellectual and operational work went into thinking through deterrence in such circumstances and the consequent weapons and delivery system requirements both to maintain deterrence and to retaliate if it failed.

A tripolar nuclear world is far more dangerous and complicated. How do we deter two nuclear threats simultaneously? Will Russia and China act as allies or behave opportunistically? Will we have enough warheads and delivery systems to handle two separate nuclear crises? We are nowhere near able to answer these questions confidently, and Cold War history should teach that we are already well behind in responding, both conceptually and operationally.

Indeed, we can only say with certainty that substantial additional nuclear warheads and delivery systems are necessary — and sooner rather than later. America must also urgently progress beyond the limited national missile defense program then-President George W. Bush launched over 20 years ago. The reality is that comprehensive homeland defense measures capabilities are inescapable when facing the combined Chinese and Russian threats. Any other conclusion is irresponsible.

One trap to avoid is believing that arms control agreements with China will solve or at least mitigate its rising threat to Washington and our allies. We should quickly jettison the alluring view, already in the air, that arms control will restrain China any more than it restrained Russia or rogue states like Iran and North Korea.

During the Trump administration , we saw the implications of China’s growing nuclear capabilities in part because the New START agreement with Moscow would expire (unless jointly extended by the parties) in February 2021, which was rapidly approaching. Clearly, New START has failed badly, and its extension would inordinately benefit Moscow over Washington. Russia had repeatedly violated the treaty, it did not cover tactical nuclear weapons, with which Russia had a huge advantage, and it did not address more recent technological advances like hypersonic cruise missiles.

Most critically, however, there is no logic to bipolar nuclear arms control treaties in a tripolar nuclear world. Why should America continue to bind itself in a treaty with Russia if China is left completely free to increase its nuclear arsenal without limit? Moscow agreed to bring China into any future negotiations, but Beijing oh-so-politely demurred, explaining modestly that its nuclear forces were not nearly so extensive as to warrant including them in a successor to New START. That’s where things remain today, notwithstanding the Biden administration’s grave miscalculation in extending bilateral New START without any changes until 2026.

Continuing to invite Chinese participation in future nuclear weapons negotiations serves one important purpose. If Beijing still declines to participate, it will demonstrate its clear hypocrisy. And if China joins the negotiations, it will almost certainly gridlock them, thus forcing U.S. policymakers to realize that protecting the United States is a matter of strategy and hardware, not ephemeral arms control agreements. The next two years are a period of vulnerability for America but provide ample time for Congress and possible 2024 presidential candidates to lay out their arguments. Let the debate begin.

John Bolton was the national security adviser to President Donald Trump between 2018 and 2019. Between 2005 and 2006, he was the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.